Putin meets Xi as Russia-China ties flourish amid tension with U.S.

Xi Jinping welcomes Vladimir Putin to Beijing - talking peace in Ukraine amid a backdrop of war and growing tension with the U.S. and NATO.

Watch CBS News

Xi Jinping welcomes Vladimir Putin to Beijing - talking peace in Ukraine amid a backdrop of war and growing tension with the U.S. and NATO.

John Dickerson reports on what to expect from the newly scheduled presidential debates, the biggest foreign threats ahead of the November election, and why the price of cocoa is so high.

Biden and Trump agree to 2 presidential debates; Man becomes first person with Down syndrome to complete 6 top marathons

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has canceled his planned foreign trips as Russia advances close to Kharkiv. Meanwhile, an additional $2 billion in U.S. military aid is expected. CBS News intelligence and national security reporter Olivia Gazis has the latest.

Biden and Trump agree to two presidential debates; Could Larry Hogan flip Maryland's Senate seat red?

The U.S. military says it's installed the temporary pier that will be used to bring humanitarian aid into Gaza, and trucks carrying the aid should begin "moving ashore in the coming days."

More than 700,000 Palestinians were displaced when modern Israel was formed. 76 years later, the war in Gaza has displaced twice as many.

Hundreds of thousands of Palestinians have fled the southern Gaza city of Rafah ahead of a long-awaited ground operation by Israel's military. Amid the ongoing war, an American doctor stuck in Gaza says President Biden isn't doing enough to stop the fighting. Imtiaz Tyab reports.

John Dickerson reports on the cross-examination of former President Trump's former fixer, a devastating bus crash in Florida, and the latest innovations coming out of Google.

Bus crash kills at least 8, injures dozens more in Florida; New Jersey quintuplets graduate from same college

Michael Cohen faces cross-examination in Trump "hush money" trial; RFK Jr. claims to qualify for Texas ballot

Secretary of State Antony Blinken visited Ukraine to try to reassure President Volodymyr Zelenskyy and other officials that U.S. aid is coming. The visit comes as Russia pushes forward with its new offensive in northern Kharkiv. CBS News foreign correspondent Chris Livesay reports.

America's top diplomat visits Kyiv, says U.S. weapons will make a "real difference" as Ukraine faces a fierce new Russian offensive

Israel's leader acknowledges that more than half of those killed in Gaza are likely civilians, as the U.N. shifts to a lower estimate of women and children victims.

Michael Cohen testifies about Stormy Daniels payment at Donald Trump's criminal trial; How conductor Xian Zhang is breaking barriers

Michael Cohen takes the stand in Trump “hush money” trial; Therapy dogs bring joy to government workers in Washington, D.C.

Israel's battle against Hamas has forced nearly 360,000 people to flee from a city they were told only months ago to seek refuge in.

Parts of Rafah are now abandoned as Palestinians who were sheltering there amid the war have been forced to flee again. Fighting has also broken out again in the northern Gaza Strip. Ramy Inocencio reports.

As the civilian death toll in Gaza continues to climb, President Biden is facing criticism both for his continued support of Israel and for limiting weapons transfers to the country. Skyler Henry reports.

Russia's Vladimir Putin has replaced his minister of defense Sergei Shoigu as he begins his 5th term in office and as his war in Ukraine heats up.

Thousands more civilians have fled Russia's renewed ground offensive in Ukraine's northeast that has targeted towns and villages with a barrage of artillery and mortar fire.

While officials worked to keep politics out of the event, the Israel-Hamas war led to controversy this year.

The Israeli military ordered people seeking refuge in east Rafah to evacuate immediately and head to designated humanitarian zones. The move comes after the Israeli war cabinet voted to expand its operation in the southern Gaza city, where millions are taking refuge.

Demonstrators chanting anti-Israeli slogans have descended on the Swedish city hosting the 2024 Eurovision Song Contest.

One member of Israel's government says Hamas loves Mr. Biden, but other Israelis worry their leaders are losing the vital war for global support.

Firearms sold by law enforcement have turned up at crime scenes thousands of times in recent years, a CBS News Investigation found.

Firearms sold by law enforcement have turned up at crime scenes thousands of times in recent years, a CBS News Investigation found.

The fifth week of Donald Trump's criminal trial in New York will end as it began: with the former president's ex-lawyer Michael Cohen on the stand.

Slovakia's populist Prime Minister Robert Fico was shot as he came out of a meeting. He was in "stable but still very serious" condition, the hospital said.

The U.S. military says it's installed the temporary pier that will be used to bring humanitarian aid into Gaza, and trucks carrying the aid should begin "moving ashore in the coming days."

A lawyer for New Jersey Sen. Bob Menendez sought to pin the blame on his wife, Nadine Menendez.

Two Republican-led House committees are set to consider a contempt of Congress resolution against Attorney General Merrick Garland on Thursday.

The president and vice president are required to file public financial reports.

Angie Harmon said she heard a gunshot and rushed outside, where she found her dog had been shot, and saw the delivery person putting a gun into the front of his pants, according to the lawsuit.

A judge has decided that a Southern California college professor will stand trial for involuntary manslaughter and battery in the death of a Jewish counter-protester during demonstrations over the Israel-Hamas war last year.

Firearms sold by law enforcement have turned up at crime scenes thousands of times in recent years, a CBS News Investigation found.

The fifth week of Donald Trump's criminal trial in New York will end as it began: with the former president's ex-lawyer Michael Cohen on the stand.

Learn more about a nearly 2-year investigation by CBS News that found former police guns have turned up at crime scenes across the country.

Two Republican-led House committees are set to consider a contempt of Congress resolution against Attorney General Merrick Garland on Thursday.

The report also highlights the financial destruction that can occur when workers take unpaid time off after being hurt or tired from the job.

Ransomware attack targeted a Nissan virtual private network, the automaker's U.S. subsidiary said.

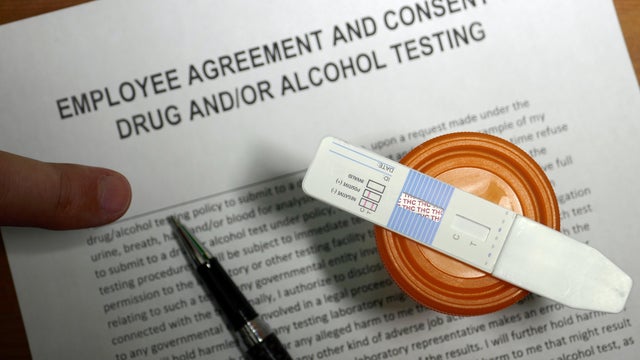

Experts call for better drug testing procedures as more states legalize marijuana and societal norms change.

McDonald's CEO Chris Kempczinski said recently the company must be laser-focused on keeping prices affordable.

What's the best place to park your money? Americans put their faith in this long-term investment, a new Gallup poll shows.

Xi Jinping welcomes Vladimir Putin to Beijing - talking peace in Ukraine amid a backdrop of war and growing tension with the U.S. and NATO.

The fifth week of Donald Trump's criminal trial in New York will end as it began: with the former president's ex-lawyer Michael Cohen on the stand.

Two Republican-led House committees are set to consider a contempt of Congress resolution against Attorney General Merrick Garland on Thursday.

Judge Juan Merchan has held Trump in contempt of court for violating the gag order 10 times, with a $1,000 fine for each violation.

The president and vice president are required to file public financial reports.

A new study finds hospitals with a higher share of women surgeons and and anesthetists shave better patient outcomes.

Experts call for better drug testing procedures as more states legalize marijuana and societal norms change.

Opioid overdose deaths decreased, but there was an increase in overdose deaths from psychostimulants like meth and cocaine.

Nurse practitioners have been viewed as a key to addressing the shortage of primary care physicians. But data suggests that, just like doctors, they are increasingly drawn to better-paying specialties.

Nearly 4,000 people die from accidental drowning ever year, according to the CDC.

Xi Jinping welcomes Vladimir Putin to Beijing - talking peace in Ukraine amid a backdrop of war and growing tension with the U.S. and NATO.

Local media reported that the victim said he had been unable to call out for help "because of a spell that his captor had cast on him."

Tens of thousands of people gathered in the Georgian capital of Tbilisi to protest the law's passage.

The U.S. military says it's installed the temporary pier that will be used to bring humanitarian aid into Gaza, and trucks carrying the aid should begin "moving ashore in the coming days."

Extreme heat is known as a "silent killer," and in some areas across Asia, its intensity would have been impossible without one critical factor, a new study found.

Angie Harmon said she heard a gunshot and rushed outside, where she found her dog had been shot, and saw the delivery person putting a gun into the front of his pants, according to the lawsuit.

Whoopi Goldberg described the book as a way to dispel speculations about her upbringing and to share her story on her own terms.

Brittney and Cherelle Griner shared videos from their baby shower exclusively with "CBS Mornings."

"Young Sheldon" will end its seven-year run with a two-episode series finale on Thursday, May 16, beginning at 8/7c on CBS.

Actor Iain Armitage joins "CBS Mornings" to discuss the series finale of the hit CBS show, "Young Sheldon."

Ransomware attack targeted a Nissan virtual private network, the automaker's U.S. subsidiary said.

The Innovation & Disruption Leaders documentary series transforms corporate buzzwords like 'tech' and 'AI' into accessible concepts. Through the power of visual storytelling, we delve into the minds of industry leaders, executives and entrepreneurs alike. Who will decide the destiny of tomorrow's business landscape? By putting business in front of the camera, these incredible films get us one step closer to the answer.

From labor shortages to environmental impacts, farmers are looking to AI to help revolutionize the agriculture industry. One California startup, Farm-ng, is tapping into the power of AI and robotics to perform a wide range of tasks, including seeding, weeding and harvesting.

A group of TikTok creators is suing to stop a new law that could ban the social media app in the U.S. The legal challenge follows another lawsuit filed by TikTok and its China-based owner.

Google's highly-anticipated, annual developer conference began Tuesday. The event focused mainly on the company's artificial intelligence advancements. Lisa Eadicicco, senior mobile editor for CNET, joins CBS News with highlights.

A new study suggests that the first warm-blooded dinosaurs may have roamed Earth about 180 million years ago.

Extreme heat is known as a "silent killer," and in some areas across Asia, its intensity would have been impossible without one critical factor, a new study found.

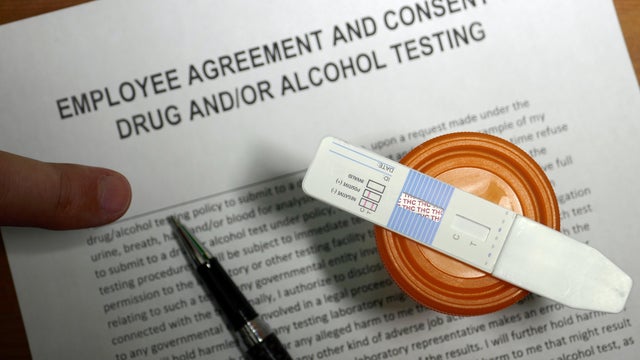

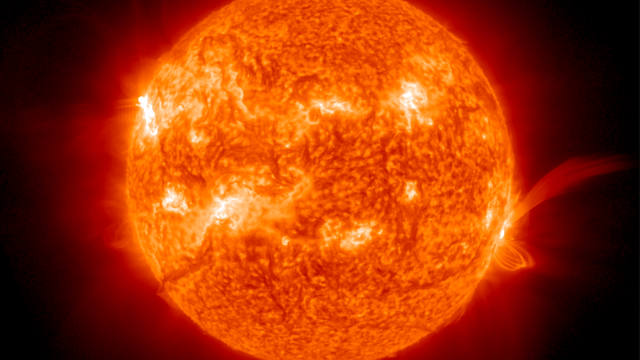

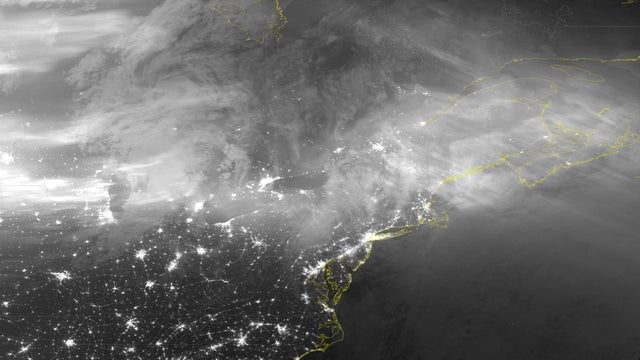

Millions of Americans looked to the night sky and snapped magical photos and videos of the northern lights this past weekend during the momentous geomagnetic storm.

Scientists who study such things have found that cicadas urinate in a jet stream because they consume an incredible volume of fluid during their brief time above ground.

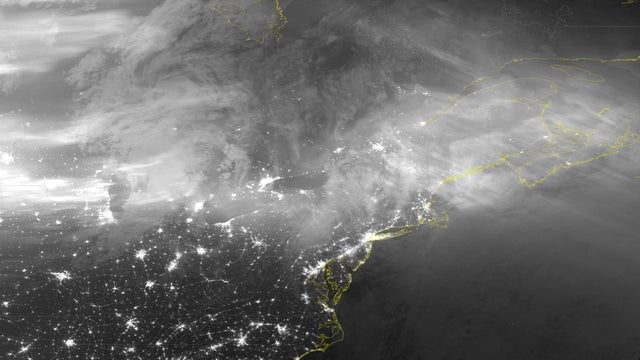

Solar storms can dazzle, bringing displays of the northern lights to large parts of the globe. But geomagnetic storms can also affect electronic systems.

Local media reported that the victim said he had been unable to call out for help "because of a spell that his captor had cast on him."

A judge has decided that a Southern California college professor will stand trial for involuntary manslaughter and battery in the death of a Jewish counter-protester during demonstrations over the Israel-Hamas war last year.

Firearms sold by law enforcement have turned up at crime scenes thousands of times in recent years, a CBS News Investigation found.

Minneapolis Police Chief Brian O'Hara says his department is short more than 200 officers, and has lost 40% of its police force in the last four years.

Assailants killed 2 prison convoy officers, springing the inmate they were escorting. France's prime minister vowed the suspects "will pay."

The large explosion of energy and light from the sun comes just days after Earth was slammed with the biggest geomagnetic storm in more than 20 years.

WASP-193b is 50% larger than Jupiter — the largest planet in our solar system — but seven times less massive because of it's extraordinarily low density.

Millions of Americans looked to the night sky and snapped magical photos and videos of the northern lights this past weekend during the momentous geomagnetic storm.

The oxygen valve that derailed a launch try last week has been replaced, but engineers want more time to verify an unrelated helium leak has been fixed.

The forecasted conditions come after a weekend of jaw-dropping northern lights seen as far south as Florida and as "magnetically complex" sunspots bigger than Earth continue to emit solar flares.

A look back at the esteemed personalities who've left us this year, who'd touched us with their innovation, creativity and humanity.

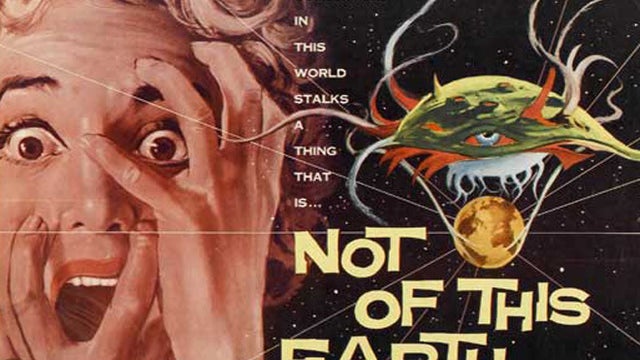

A look back at the hallowed career of the indie "B-movie" filmmaker, known for exploitation films, monster flicks, and some bizarre movie posters.

Despite losing three quarters of the blood in her body, Donna Ongsiako was able to help police find the person who almost took her life.

The Francis Scott Key Bridge in Baltimore collapsed early Tuesday, March 26 after a column was struck by a container ship that reportedly lost power, sending vehicles and people into the Patapsco River.

When Tiffiney Crawford was found dead inside her van, authorities believed she might have taken her own life. But could she shoot herself twice in the head with her non-dominant hand?

The Supreme Court ruled Wednesday that Louisiana can use a newly-drawn House map that includes a second district with a majority of Black voters. The decision comes after a lower court recently called the map unconstitutional racial gerrymandering. CBS News congressional correspondent Nikole Killion has more.

Presidential debates have become a standard part of the four-year contest, but this contest is anything but standard. With two debates finally on the calendar, the two qualifications for a good debate are also two issues totally up for grabs in U.S. democracy. CBS News chief political analyst John Dickerson explains.

Higher cocoa prices are hitting chocolate lovers' wallets. CBS News reporter Taurean Small explains what's driving the increase, and what chocolate brands are doing to adapt.

Many high school seniors in 2020 never got to participate in a big graduation ceremony due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Now, four years later, caution about protests over the war in Gaza means some won't get a college ceremony either. CBS News' Meg Oliver reports on the "no graduation" generation.

Between dual overseas wars, rising competition with China and a struggle to find consensus on southern border policy, the next president will be tasked with handling many homeland security issues. CBS News national security contributor Sam Vinograd joins to discuss some of the major challenges the winner of the November election will face.